Strategy 1: Use rflip()

WHEN can we use this method?

- ONLY if the parameter of interest is ONE PROPORTION.

Example:

502 People were given 2 sets of photos of owner/dog pairs - one really owner-dog, and one just a random person + dog – and asked to choose the real pair. The sample statistic was the proportion correct which was 0.8. We want to test: \[H_0: p = 0.5\] \[H_A: p \neq 0.5\]

So we want many sample proportions from a hypothetical population that is like the real sample as much as possible, except that \(H_0\) is true, so \(p=0.5\).

So notice that the prob input to rflip matches the null hypothesis, and not the sample stat.

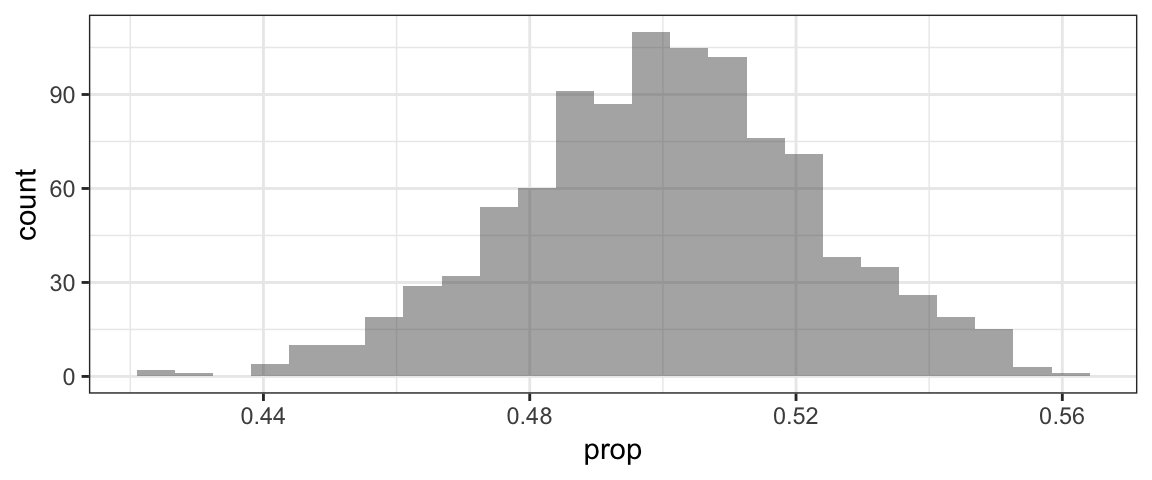

RSD1 <- do(1000)*rflip(n = 502, prob=0.5)

head(RSD1) #to see variable namesgf_histogram(~prop, data=RSD1) Once we have the randomization distribution, we need to find the p-value: the probability of getting a sample stat \(\hat{p}\) at least as extreme as 0.8, from the samples in the randomization distribution.

Once we have the randomization distribution, we need to find the p-value: the probability of getting a sample stat \(\hat{p}\) at least as extreme as 0.8, from the samples in the randomization distribution.

p.value1 <- prop(~prop >= 0.8, data=RSD1)

#because alternate is 2-sided:

# we need both "tails"...

# a value of 0.2 is as far from the H0 value of 0 as 0.8 is!

p.value2 <- prop(~prop <= 0.2, data=RSD1)

p.valueA <- p.value1 + p.value2

p.valueA## prop_TRUE

## 0Alternatively, we could just double the one-sided p-value, because the sampling distribution (should be) symmetric:

p.valueB <- 2*prop(~prop >= 0.8, data=RSD1)

p.valueB## prop_TRUE

## 0The values should be almost the same. Here, what does it mean to get a p-value of 0? A value as extreme as the sample stat was never seen in the randomizations! However, we only did 1,000. So instead of reporting a p-value of 0, it would be better to say that the p-value is less than 0.001.

Strategy 2: Shuffle category labels

WHEN can we use this method?

- Whenever the parameter of interest involves a difference between groups.

Example:

Is the proportion marmots who whistle different when they encounter hikers with dogs, rather than those without?

We want to test: \[H_0: p_{dog} - p_{no dog} = 0\] \[H_1: p_{dog} - p_{no dog} \neq 0\]

First, we will read in the data and compute the sample stat.

marmot <- read.csv(file='http://www.calvin.edu/~sld33/data/marmot.csv')

#get a table of proportion whistles by hiker type:

tally(~whistle | hiker, data=marmot, format='prop')## hiker

## whistle dog nodog

## no 0.05 0.40

## yes 0.95 0.60#what about just the SECOND ROW of the table (where whistle='yes')?

tally(~whistle | hiker, data=marmot, format='prop')[2,]## dog nodog

## 0.95 0.60#so what is the sample difference in proportions

# (from the real data)?

diff(tally(~whistle | hiker, data=marmot, format='prop')[2,])## nodog

## -0.35Now do the randomization, computing the same quantity (difference in proportion whistlers, by hiker type) but with shuffled dog/no dog hiker labels:

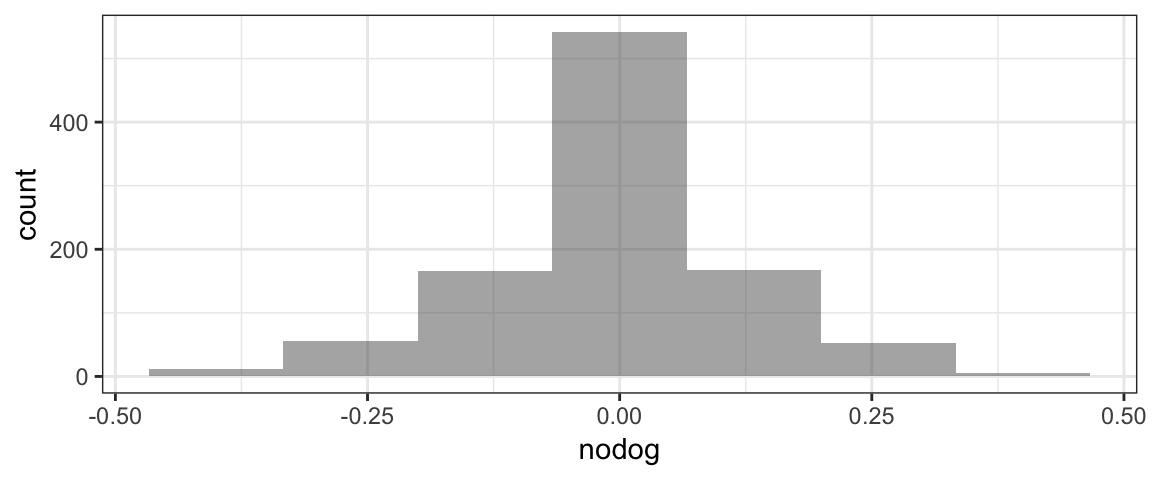

RSD2 <- do(1000)*diff(tally(~whistle | shuffle(hiker), data=marmot, format='prop')[2,])

#see variable names:

head(RSD2)gf_histogram(~nodog, data=RSD2, bins=7)

p.value <- 2*prop(~nodog <= -0.35, data=RSD2)

p.value## prop_TRUE

## 0.022Strategy 3: Re-center data

WHEN can we use this strategy? It works when the parameter of interest is a single mean (or a median, or a standard deviation, or an IQR, or…ANY other single parameter except for a proportion. For a proportion, use the rflip() strategy instead.)

Example:

Subway claims to sell foot-long subs…but are they really? Some people brought a class-action lawsuit against Subway alleging that their subs were really less than a foot long. They might want to use data on the measured length of a bunch of Subway subs to test: \[H_0: \mu = 12\] \[H_1: \mu < 12\]

(where \(\mu\) is the true overall mean of all Subway subs in the world.) They chose a one-sided alternate because it won’t help the law suit at all if the subs are actually bigger than Subway claims – the claimants only care if they are shorter!

subway <- read.csv(file='http://www.calvin.edu/~sld33/data/subway.csv')

head(subway) #to see variable namesmean(~length, data=subway)## [1] 11.2999#make a new dataset with mean length 12

subway$length12 <- subway$length + 0.7

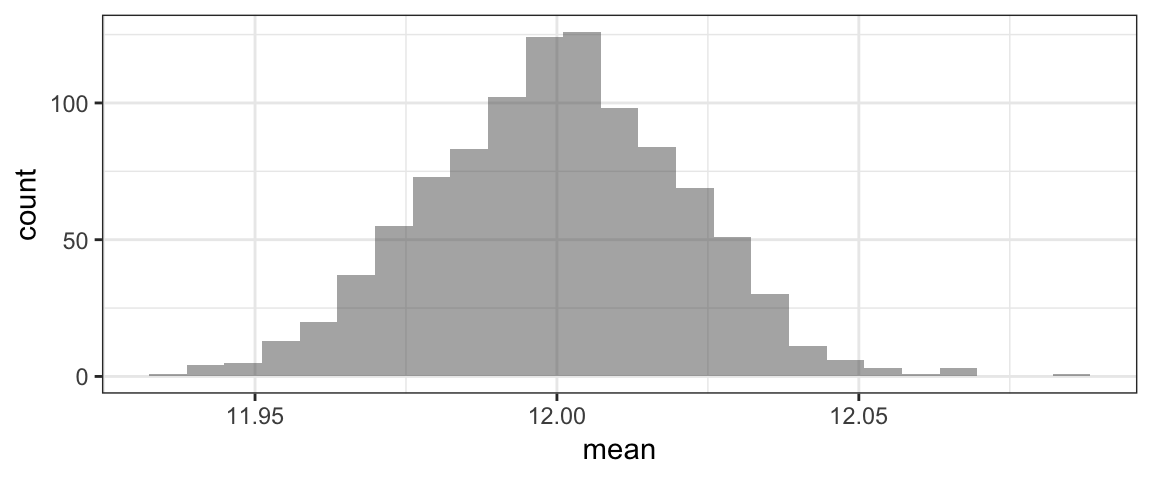

RSD3 <- do(1000)*mean(~length12,

data=sample(subway,

size=nrow(subway), replace=TRUE))

head(RSD3)gf_histogram(~mean, data=RSD3)

#find p-value: one-sided

prop(~mean <= 11.3, data=RSD3)## prop_TRUE

## 0#find p-value: 2-sided

2*prop(~mean <= 11.3, data=RSD3)## prop_TRUE

## 0Strategy 4: Multiply all differences randomly by +1 or -1

WHEN can we use this method?

- Only for paired data. This happens if the variable of interest is a difference between two observations of the same case or subject, and your parameter of interest is the mean (or some other summary) of these differences. For example, if you measure the weight of 100 women at the start of pregnancy and then one year after birth, and compute the difference for each person, you might be interested in the mean of those differences. Or if you study 50 bee hives and for each one, find the difference in proportion drones (male bees) in summer and winter, you might be interested in testing whether the mean seasonal difference in proportion drones, averaged over the 50 hives, is 0 or not.

In class, we considered an experiment with marmots. Each marmot was tested in two experiments: once it was approached by a hiker without a dog, and once by a hiker with a dog. The researchers recorded the distance which the marmot ran away in each experiment. The variable of interest was the difference in flight distance with/without a dog; the parameter of interest was the true population mean difference in flight distance, \(D = \mu_{diff}\) where \(\mu_{diff}\) is the mean of differences in flight distance for all marmots in the population.

marmot2 <- read.csv(file='http://www.calvin.edu/~sld33/data/marmot2.csv')

#sample statistic

mean(~ddist, data=marmot2)## [1] 47.21818#rand. dist

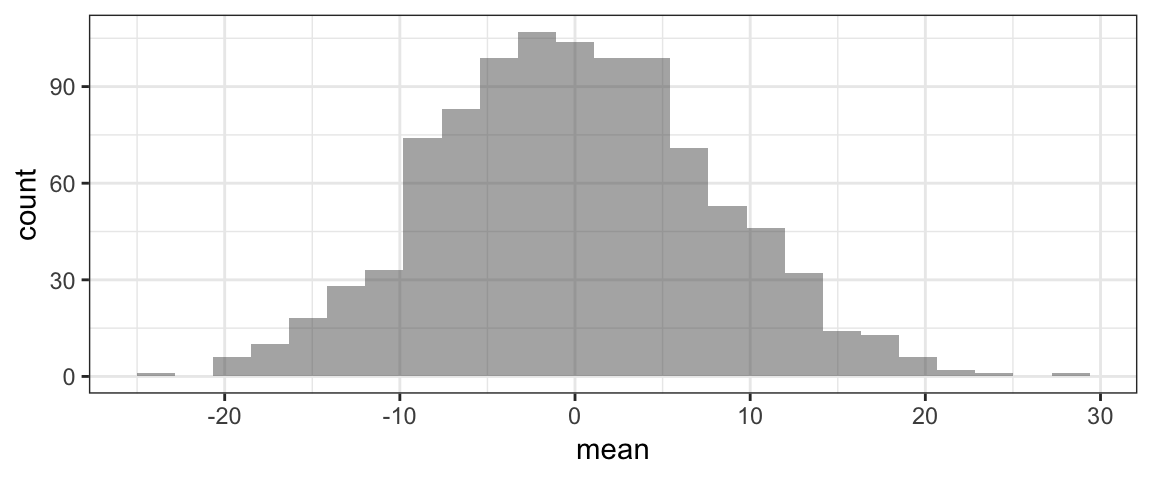

RSD4 <- do(1000)* mean(~ddist*

sample( c(-1,1) ,

size=60,

replace=TRUE),

data=marmot2)

gf_histogram(~mean, data=RSD4)

#p-value:

prop(~mean >= 47, data=RSD4)*2## prop_TRUE

## 0As usual, if the computed p-value is 0, we can report it to be “less than [1/number of randomizations we did]*[2 if H1 is 2-sided]" so here, the p-value must be less than 2/10,000 = 0.0002.

Reporting Results

There are a few important things to include when reporting the results of a hypothesis test.

- Somewhere in your answer, report the hypotheses you are testing, and also report the sample statistic from the data. This gives people a first impression for how large the difference between the sample stat and the \(H_0\) value is, which helps them form opinions about whether results are practically significant as well as (possibly) statistically significant!

- Report the p-value you obtained.**

- State in words what the p-value tells you. For example, in the Subway example, if we got a p-value of 0.01, we might say: The p-value of the test was 0.01, which means that if Subway subs were really 12 inches long on average, there would be only a 1% chance of getting a dataset like ours, where the sample mean sub length was only 11.3 inches.

- State your decision: do you reject the null hypothesis or fail to reject the null hypothesis? (Remember, small p-values are evidence against the null, so a small p-value leads you to reject \(H_0\).) If using a threshold \(\alpha\), the usual standard is to use \(\alpha = 0.05\), but 0.01 is also sometimes used. In this case, if the p-value is less than \(\alpha\), then reject the null. If you are using a weight-of-evidence approach rather than a threshold, then you need to make a judgment call about whether the p-value you found is “small” or not; if it is “small” then you reject the null.

- Explain what the decision means in context. For example, for the Subway case, we might say: Since the p-value is small, we reject the null hypothesis that the true mean sub length is 12 inches. The data provide evidence in favor of the alternate hypothesis, suggesting that Subway subs are less than 12 inches long. If we had instead gotten a p-value of 0.45 in the Subway test, we might then say: Since the p-value is large, we fail to reject the null hypothesis; the data provide no evidence against the idea that the true mean length of Subway subs is 12 inches.